Introduction:

The increasingly innovative technological advancements occurring in the medical world today have opened doors for expanding fields of medicine that are now being used to approach common health issues in ways that they have never been thought of before.

An example of a field that is continuing to reinvent itself with newer technology is preventative medicine. This is seen with experts in the field like Dr. Michael Snyder from Stanford Medicine who is working with wearables (a form of advanced technology that people can wear on their bodies) in order to profile individuals to improve early detection of health issues. It is possible these advances in wearables and early identification of diseases can be leveraged to help prevent the cancers caused by genetic abnormalities that often go undetected until it’s too late.

This paper will discuss how DNA replication and the cell regulation cycle work, going specifically into BRCA 1 and 2 Gene Regulators and the impact of their mutations, and how understanding these genomes and associated mutations may be addressed by the latest approaches in preventative medicine.

DNA Replication:

According to the National Library of Medicine, DNA replication occurs within the process of the cell cycle as cells are dividing and multiplying because the new daughter cells need their own copies of DNA in order to continue replicating in the future.

Within this cycle of replication, there are regulation checkpoints along the way to ensure that there are no errors in the process. These regulation checkpoints occur in the G phases of the cell cycle and they function as surveillance to ensure the cell grows to the right size, the cell equally separates in mitosis, and that all of the chromosomes that contain genes are replicated correctly. These checkpoints are fueled by the presence of cyclin-dependent kinases (or CDKs) which, once activated by their cyclin subunits, move the cycle forward.

However, these CDKs can also be restricted from binding to their cyclin subunits in the case that there is an issue recognized by a checkpoint which leads to the binding of inhibitory proteins (CKIs). The checkpoints essentially release these inhibitory proteins if they recognize any issues present. Specifically in the G1 phase is where DNA replication damage response takes place. In this response, tumor suppressors work to target double stranded DNA breaks and if there is no other option, initiate cell death.

However, sometimes these checkpoints can malfunction which can result in irregularities in DNA replication going unnoticed and passing through the cycle. The products of these unchecked cells can be cancerous.

BRCA 1 and BRCA2 Mutations:

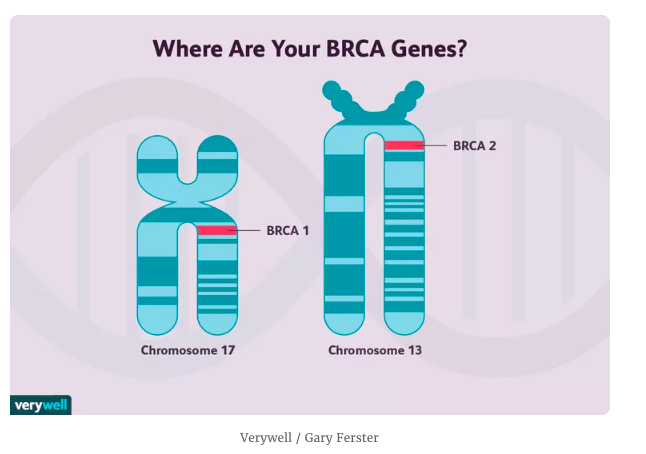

As stated by the National Human Genome Research Institute, in gene replication, BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 function as tumor suppressor genes, which means they encode certain proteins used to regulate cell division at different checkpoints. If one of these genes develops or originally has a mutation, the production of those proteins that regulate the cell cycle can be inactivated or lead to the proteins not being produced correctly.

The American Cancer Society indicates that when errors do arise in this cell division process, this means that due to these mutations there are no functioning genes to recognize it and create proteins to slow or stop cell proliferation and repair cell DNA. Without these checkpoint proteins, DNA repair mechanisms may not be initiated and the cell regulation process will proceed without fixing any problems. This leads to abnormal cell growth, which can be cancerous.

BRCA1 and 2 Mutation Risks

What are the implications of having BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations? As stated above, the mutation can lead to the development of cancer cells. Individuals with the mutation have much higher risks of developing certain cancers in their lifetime because they are more susceptible to uncontrollable cell proliferation.

According to the Basser Center for BRCA at Penn Medicine, the risk of breast cancer of an average woman is about 13 percent, while women with a BRCA 1 mutation have a risk up to 75 percent and women with a BRCA 2 mutation have a risk up to 70 percent. Similarly, the risk of ovarian cancer for an average woman is 1-2 percent, those with BRCA1 mutation have 30-50 percent chance and with BRCA2 mutation it is 10-20 percent. Even though these are some of the more common cancers found with BRCA mutations, there are also increased risks of developing fallopian tube, pancreatic, skin, and peritoneum cancers.

Men with the mutation also have an elevated risk of cancers involving the pancreas, breast, prostate, and skin. The average male has a 0.1 percent risk of breast cancer but with BRCA1 that increases to 1-5 percent and, with BRCA2, that increases to 5-10 percent. Most men with a mutation have increased prospects of prostate cancer which can go from 16 percent for an average man to 15-25 percent with the BRCA2 mutation and generally occur much earlier and more aggressively.

Both men and women with BRCA 1 mutations are at a 2-3 percent risk, or, with BRCA 2 mutations, are at a 3-5 percent risk of pancreatic cancer compared to the average population at 1 percent.

Accompanying Table:

| Type of Cancer | Risk with BRCA1 for Women | Risk with BRCA2 for Women | Average Woman | Risk with BRCA1 for Men | Risk with BRCA2 for Men | Average Man |

| Breast Cancer | 60-75% | 50-70% | 13% | 1-5% | 5-10% | 0.1% |

| Ovarian Cancer | 30-50% | 10-20% | 1-2% | – | – | – |

| Prostate Cancer | – | – | – | – | 15-25% | 16% |

| Pancreatic Cancer | 2-3% | 3-5% | 1% | 2-3% | 3-5% | 1% |

| Melanoma | 3-5% | 1-2% | 3-5% | 1-2% |

Preventative Surgeries and Screening for BRCA Mutations:

There are many options for individuals who want to take preventative measures to lower their risk of developing cancer. These include surgery, medications, and screenings. As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists states, four of the most common preventative surgeries for women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations are bilateral mastectomies (removal of both breasts), bilateral salpingo-oophorectomies (removal of both fallopian tubes and ovaries), bilateral salpingectomies (removal of both fallopian tubes), and oophorectomies (removal of one or both ovaries).

In addition to these surgeries, there are also effective medications that patients can take in order to reduce the risk of developing breast cancers, such as Tamoxifen, which blocks the influence of estrogen on cancer cell growth for breast cancer. For ovarian cancer, the National Cancer Institute shows that use of oral contraceptives have been found to lower the risk of ovarian cancer by 30-50 percent. The least invasive preventative measure is screening. For breast cancer, this includes clinical breast exams from personal doctors and annual breast imaging starting at the age of twenty five. However, screening for ovarian cancer is much less effective than for breast cancer.

One type of screening is blood tests which may detect levels of a marker called CA-125 produced by cancer cells. Another type of screening for ovarian cancer is abdominal ultrasounds. Yearly screening for melanoma is also recommended. For pancreatic cancer, the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services states there are options for frequent imaging tests such as MRIs and endoscopic ultrasounds, however, it is a very difficult cancer to diagnose in its early stages. It is important to note that these screenings are not always reliable and do not have a sufficient ability to detect cancer at earlier stages.

Weighing the Pros and Cons:

Preventative surgeries for ovarian and breast cancer are difficult, life changing choices for women. Loss of ovarian function, according to an article titled Oophorectomy: the debate between ovarian conservation and elective oophorectomy in the National Library of Medicine, can have negative impacts on a woman’s body long term, although some of these may be offset with hormone replacement therapy, since the ovaries have the function in a woman’s body of producing hormones.

The negative side effects of having ovaries removed are not being able to have children, possible bone density loss, cognitive impairment, increased risk of osteoporosis, and cardiac mortality. Anticipating the impact of ovary removal is difficult as every woman’s body reacts differently to the loss of their ovaries and it’s hard to know the exact repercussions. However, ovaries are not an essential organ for the body so fully removing them to almost completely reduce the risks of ovarian cancer may outweigh the possible negative side effects. This is especially true because the other methods of prevention, such as screening, are not guaranteed to detect cancer.

As stated before, screenings for ovarian cancer are not advanced enough to always detect early forms of cancer so there is a good chance once detected that it could be too late. Bilateral mastectomies may also come with their own set of challenges and risks for a woman’s body, however, both of these surgeries will significantly reduce the woman’s chance of having ovarian or breast cancer.

Preventive Medicine: A hope for the future

There are many avenues for research involving mRNA, immunotherapy, and CRISPR that may end up leading to vaccines or cures for many hard to treat diseases. For example, advances in genomics have led to significant new information on genetic links to diseases in the human body. Current research with advances in preventative medicine may lead to improved detection of diseases related to genetic mutations.

According to American College of Preventive Medicine, preventative medicine is defined as healthcare related measures that can be taken in order to protect a patient’s health and try to reduce or avoid certain medical issues. Using this approach, medical professionals are able to evaluate the patient and, with their expertise, they are able to suggest the appropriate preventative medicine approach needed. For example, Dr. Michael Snyder is working on personalized healthcare based on medical data recorded on wearables. He is using data to learn more about what occurs when people are in the transition from being healthy to being sick by creating individual healthcare profiles so that it is easy to detect shifts in an individual’s health.

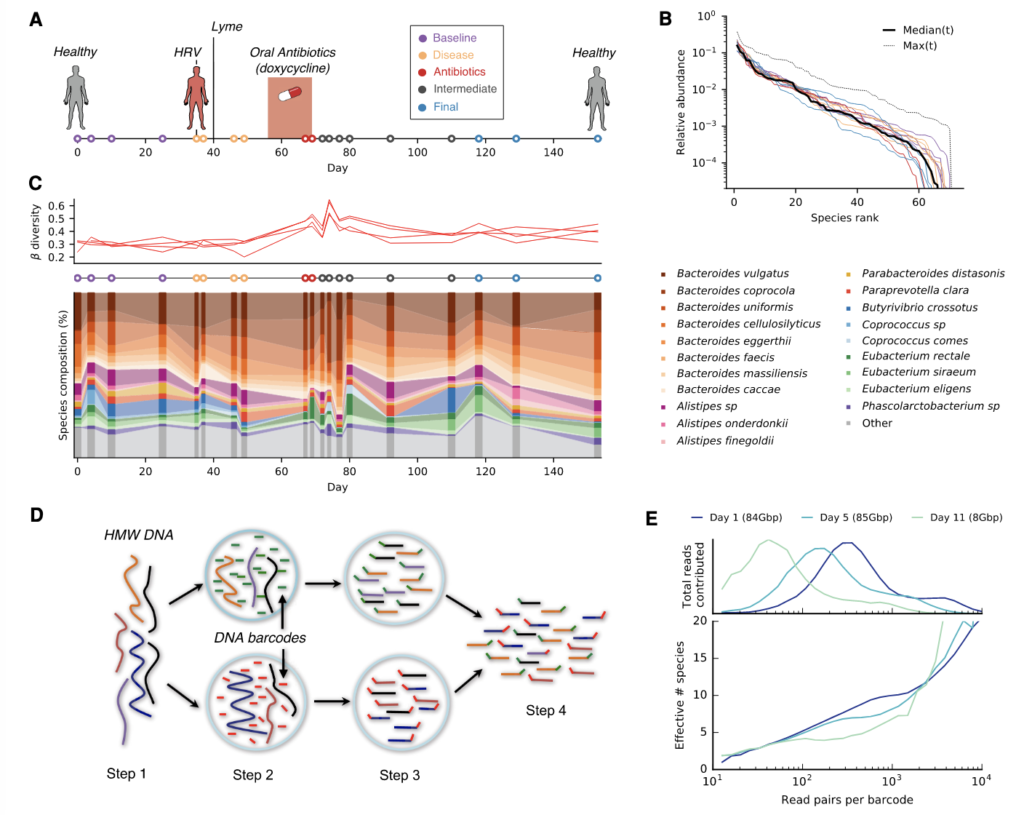

Someday, just as Dr. Snyder was able to predict his own Lyme disease diagnosis, this work may be used to predict the onset of a consequence of the BRCA 1 and 2 mutations before they become problematic for an individual.

In one of his studies titled, “A Longitudinal Big Data Approach for Precision Health”, he demonstrates how data collected through individualized profiling of omics, such as genomics, and samples taken through wearables identified important indicators of changes in individuals’ health to detect pre-cancers and cardiovascular and metabolic concerns. Through his work he discovered that most people start out with underlying conditions before becoming symptomatic. This demonstrates how a professional in the preventative medicine field such as Dr. Snyder is able to use medical data to support decisions about how to maintain the well-being and health of patients.

According to Penn Medicine, recent advancements in “single-cell sequencing technologies” have allowed researchers to start to be able to monitor changes in individual cells, which Robert Vonderheide, director of the University of Pennyslvania’s Abramson Cancer Center, states will “allow them to find these needles in the haystack”, referring to their new ability to detect these difficult to find, potentially dangerous, premalignant cells early on.

Researchers Erica Carpenter, director of the Liquid Biopsy Laboratory at the Abramson Cancer Center, and Bryson Katona, director of the Gastrointestinal Cancer Genetics and Cancer Risk Evaluation Programs, are working to find new “blood based biomarkers” (this includes a tumor marker (CA-19-9), extracellular vesicles, and circulating tumor DNA), combine them, and create an “algorithm” that they can use to decipher patterns across these biomarkers.

Susan Domchek, the executive director at the Bassar Center for BRCA at the Abramson Cancer Center, is testing a vaccine with BRCA positive patients that have never had cancer in hopes that it will prevent the onset of breast cancer. This vaccine, originally for patients that were in remission, was created in the hopes of intercepting a recurrence of cancer but is now being tested on BRCA positive patients who haven’t had cancer in the hopes of preventing “early lesions before tumors develop”. In addition, Moderna has come out with information regarding the first mRNA vaccine for melanoma that is in the midst of phase three clinical trials right now, with encouraging results from their phase two trials.

These new hopes for the future start with scientists and researchers like Dr. Snyder focusing on precision medicine and promoting proactive health strategies that can lead to actively detecting and preventing illnesses instead of waiting until it’s too late.

Katie Spitzer is a junior at Palo Alto High School. She has always been intrigued by biology and especially genetics and genome editing. The topic of genetic mutations is personal, as someone who has the BRCA mutation in her family. She finds the new research in these fields very exciting and plans to be involved with similar research as a scientist. Outside of science, she also enjoys helping others enjoy her passions of playing competitive water polo and doing competitive swimming.

Works Cited:

“About Preventive Medicine.” ACPM, www.acpm.org/about-acpm/what-is-preventive-medicine/#:~:text=Preventive%20medicine%20is%20the%20practice,Medical%20doctors%20(MD).

Barnum, Kevin J, and Matthew J O’Connell. “Cell Cycle Regulation by Checkpoints.” Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.), 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4990352/.

Bell, Daphne W. “Tumor Suppressor Gene.” Genome.Gov, www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Tumor-Suppressor-Gene.

“BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations.” ACOG, www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/brca1-and-brca2-mutations#:~:text=BRCA1%20and%20BRCA2%20are%20tumor,which%20can%20lead%20to%20cancern.

“BRCA in Women.” BRCA in Women | Basser Center, www.basser.org/brca/brca-women.

“Breast Cancer Risk Factors You Can’t Change.” Breast Cancer Risk Factors You Can’t Change, www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/risk-and-prevention/breast-cancer-risk-factors-you-cannot-change.html#:~:text=BRCA1%20and%20BRCA2%3A%20The%20most,which%20can%20lead%20to%20cancer .

“Cell Cycle Control.” Cell Cycle Control – My Cancer Genome, www.mycancergenome.org/content/pathways/cell-cycle-control/.

Erekson, Elisabeth A, et al. “Oophorectomy: The Debate between Ovarian Conservation and Elective Oophorectomy.” Menopause (New York, N.Y.), Jan. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3514564/.

Lynne Eldridge, MD. “How Having a BRCA Mutation Affects Breast Cancer Risk.” Verywell Health, Verywell Health, 23 Mar. 2022, www.verywellhealth.com/brca-mutations-and-breast-cancer-4158206.

“News Details.” Merck and Moderna Initiate Phase 3 Study Evaluating V940 (mRNA-4157) in Combination with KEYTRUDA® (Pembrolizumab) for Adjuvant Treatment of Patients with Resected High-Risk (Stage IIB-IV) Melanoma, investors.modernatx.com/news/news-details/2023/Merck-and-Moderna-Initiate-Phase-3-Study-Evaluating-V940-mRNA-4157-in-Combination-with-KEYTRUDA-pembrolizumab-for-Adjuvant-Treatment-of-Patients-with-Resected-High-Risk-Stage-IIB-IV-Melanoma/default.aspx

“Oral Contraceptives (Birth Control Pills) and Cancer Risk.” National Cancer Institute, www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/hormones/oral-contraceptives-fact-sheet#:~:text=Ovarian%20cancer%3A%20Women%20who%20have,contraceptives%20(16%E2%80%9318).

“Pancreatic Cancer.” Pancreatic Cancer | Cancer Screening and Prevention | Health & Senior Services, health.mo.gov/living/healthcondiseases/chronic/cancer/pancreatic-cancer.php

Roy, Rohini, et al. “BRCA1 and BRCA2: Different Roles in a Common Pathway of Genome Protection.” Nature Reviews. Cancer, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 23 Dec. 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4972490/.

Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose, Sophia Miryam, et al. “A Longitudinal Big Data Approach for Precision Health.” Nature News, 8 May 2019, www.nature.com/articles/s41591-019-0414-6.

Snyder Lab. “Research.” Snyder Lab, med.stanford.edu/snyderlab/research.html.

Snyder, Michael “Dr. Michael Snyder on How the Healthcare System Is Broken (and How Deep Profiling Can Help).” YouTube, 16 July 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=V1h6JCzoiJ0.

Weir, Kirsten. “Can We Intercept Cancer? A New Frontier in Cancer Research.” Pennmedicine.Org, www.pennmedicine.org/news/news-blog/2023/february/can-we-intercept-cancer-a-new-frontier-in-cancer-research.