Note: Any similarity in this text is due to the maintenance of the original paper’s style. All information credit goes to the authors of the study, as well as supplementary sources.

Research Authors:

Xiao Li, Dalia Perelman, Ariel K. Leong, Gabriela Fragiadakis, Christopher D. Gardner, and Michael P. Snyder

Abstract:

In today’s society, obesity has become increasingly common, affecting more than two in every five Americans. Obesity results in an exponentially higher risk of developing heart disease, stroke, and other diseases. Previous studies show that a majority of obese individuals can lose weight in the short-term. However, many soon gain back a significant amount of weight after losing it. Recently, scientists have begun exploring the impact of food quality, as well as quantity, on obesity. Obesity, in turn, can cause inflammation and problems with certain biochemical pathways, making it harder to lose weight. Additionally, the type of bacteria in an individual’s gut microbiome – the collection of bacteria and microorganisms in the digestive system – can also contribute to obesity and the ability to break down nutrients such as carbohydrates and fats. This study reviews the impact of different dietary and non-dietary factors on weight loss.

Methods:

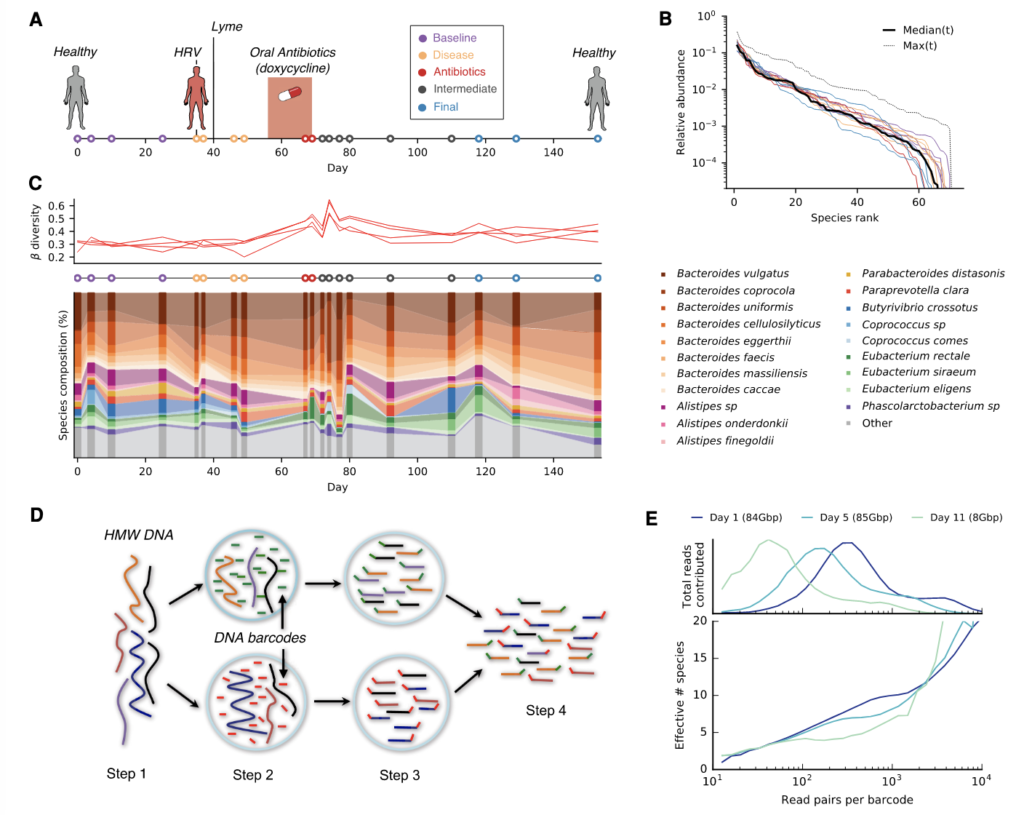

To fully explore different factors in weight loss, data from the DIETFITS study were analyzed. This was a study in which 609 individuals were split into two healthy diets: a carbohydrates-restrictive diet (HLC) and a fats-restrictive diet (HLF) for 1 year. The research showed similar weight loss between groups but high variability within groups. In this study, different aspects that may indicate an individual’s ability to lose weight were sampled. Sampling occurred three times: baseline, 6-months, and 12-months. Blood samples were used to identify molecules that could indicate potential biological mechanisms associated with weight loss. Fecal samples were collected from 49 individuals to examine the contents of their gut microbiomes. Other factors, such as diet and body composition were also measured. The researchers found that certain molecules and microbes play a large role in maintaining weight loss. A key fact about this study was that all participants strictly followed their assigned diet throughout the whole study.

Results:

For some context on the DIETFITS study, a majority of participants consumed fewer calories 6 months after beginning the study, and continued to maintain these numbers through 12-months. The low-carbohydrate group consumed more calories from protein than the low-fat group.

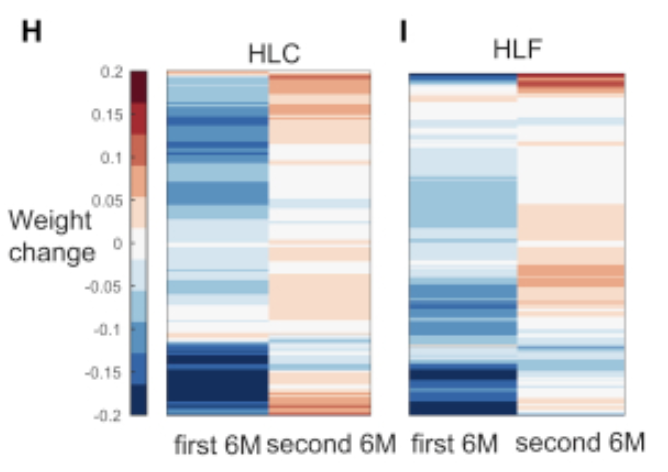

The researchers found that the median amount of weight lost was more for the low-carbohydrates group as compared to the low-fat group in the first 6 months of diet. However, the weight loss differences between the groups were not significant after 12 months. This indicates that in the second 6 months of the diet, the low-fat diet was better for losing and maintaining weight than the low-carbohydrate diet.

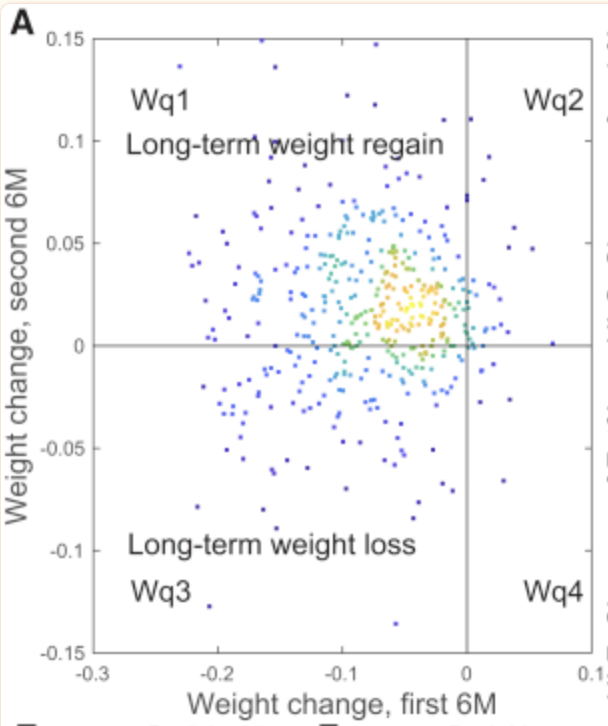

There were a few different ways individuals progressed or regressed during their weight loss journeys in these 12-months. As the above graph shows, many in the low-carbohydrate diet lost weight temporarily and subsequently gained it back. But why is this?

To begin, the researchers focused on the first six months of the diets, when most of the weight loss occurred, to determine potential causes.

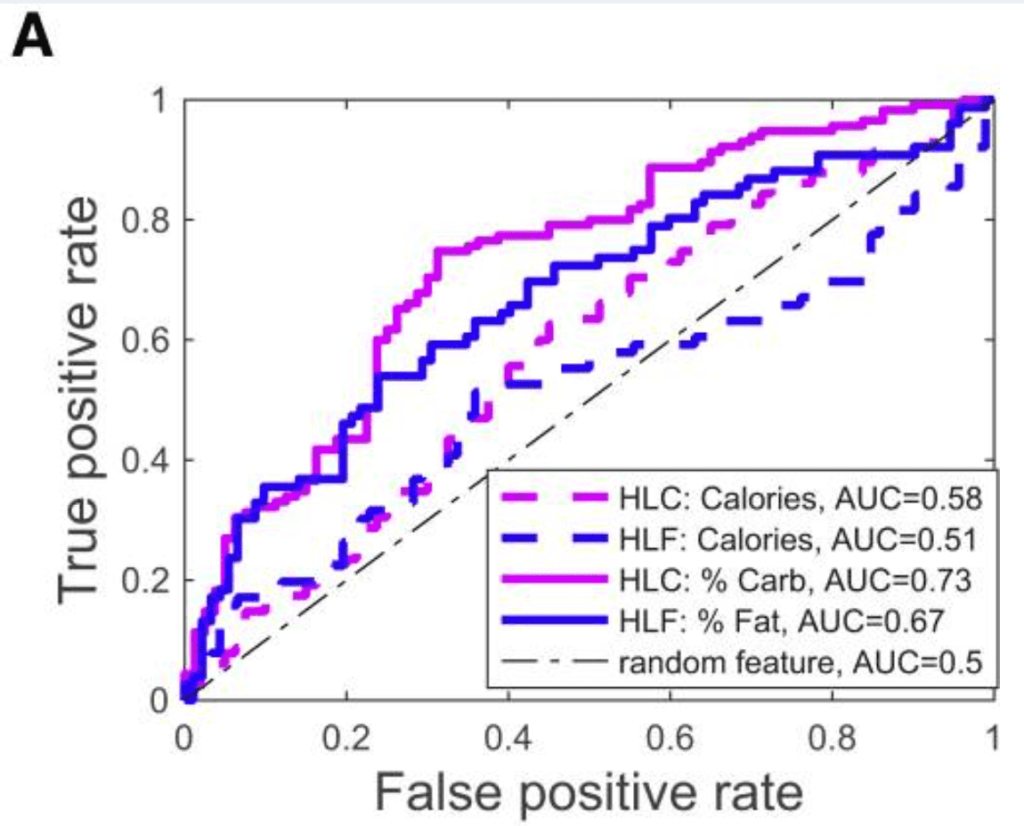

As the above chart shows, the area under the curve (AUC) for the % of certain nutrients (0.73 for carbohydrates and 0.67 for fat) was higher than for calories (0.58 for HLC and 0.51 for HLF). Based on these results, the researchers determined that the contents of the diet played a larger role in weight loss than the number of calories consumed themselves.

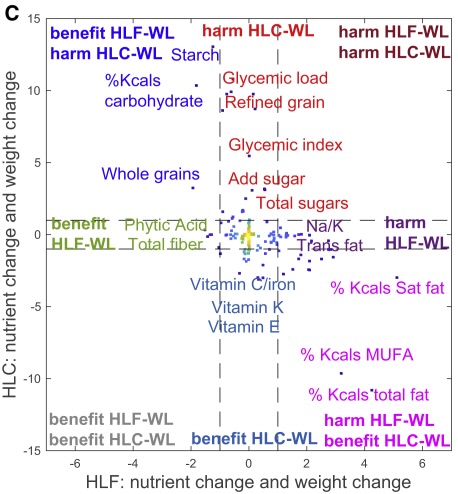

As the above figure illustrates, different nutrients affect weight loss in different ways. For example, whole grains were shown to be beneficial for weight loss in the low-fat diet, but harmful for weight loss in the low-carbohydrate diet. There were some nutrients that were beneficial for only one of these two diets, whereas there were some that were beneficial for both diets.

In the low-carbohydrate diet, high amounts of fat and low amounts of carbohydrates were associated with weight loss. Additionally, fiber was shown to not lead to weight gain. Nutrients such as vitamins K and E were also shown to be effective for weight loss in this group. Furthermore, consumption of monounsaturated fats (found in foods such as avocados and nuts) was shown to be better for weight loss than consumption of saturated fats (found in foods such as butter or beef).

In the low-fat diet, unprocessed carbohydrates were associated with weight loss. Additionally, a low ratio of sodium to potassium was associated with weight loss. This means that more potassium (found in foods such as bananas and avocados) relative to sodium (found in foods such as ham or canned soups) may help with weight loss in the low-fat diet.

Strictly following both diets increased the chance of losing weight, and also demonstrated that the type of dietary carbohydrate in the low-fat diet and the type of dietary fat in the low-carbohydrate diet were important to weight loss. This further reveals that diet quality, for example moving towards plant-based foods as opposed to processed foods, is an important factor in weight loss.

Respiratory quotient (RQ) is a ratio that compares carbon dioxide breathed out with oxygen breathed in. High carbohydrate intake results in a high RQ, whereas high fat intake results in a lower RQ. This was verified by the low-carbohydrate group, as their RQ decreased when they reduced their carbohydrate intake. A decreased RQ during the diet intervention was associated with weight loss.

There was not a significant change in RQ for the low-fat diet. There was also no relationship between RQ and weight loss for the low-fat diet group. One point of relevance was that the trends in RQ over time varied noticeably and uniquely amongst individuals. However, there was no overall relationship between RQ and fat content in both diets. This might indicate that there are certain individualized mechanisms of macronutrient digestion (used for fuel).

Theoretically, the dietary fat of those in the HLC diet would increase, because they weren’t eating carbohydrate-rich foods, and their RQ would decrease. Of the HLC participants, only 55.4% fit into this category, however (Q1). Some had low-fat consumption (high-carbohydrate consumption) and low RQ, and others had high dietary fat consumption and high RQ, which was a surprising finding. These same participants had a higher blood insulin level after consuming sugars, showing that different individuals use fats and carbohydrates in different ways. This opens new possibilities for precision medicine studies investigating how to personalize diets to these unique mechanisms.

As the chart above shows, those with a reduction in RQ and an increase in dietary fat (decrease in carbohydrates) lost the most weight. People who lost the most weight through the HLC diet tended to initially have a high RQ ratio, indicating a high carbohydrate intake, as well as a low dietary fat intake at baseline. However, those with initially low RQ scores, and thus low carbohydrate intake did not lose as much weight. HLC diet will likely work for those with high carbohydrate diets, but not for those with initially low carbohydrate diets.

Overall, those with a higher RQ lost more weight through the low-carbohydrate diet than the low-fat diet. In general, this indicates that for those with a high-carbohydrate diet, the HLC diet is more effective for weight loss than the HLF diet.

91.9% of people lost weight during the first 6 months, and 27.2% of people kept losing weight during the second 6 months. The difference between those who regained weight (Wq1 below) and those who lost weight long-term (Wq3 below) was not related to how firmly they were following the diet Those in Wq3 lost more weight than Wq1 in the 12-months. There were no significant differences in potentially confounding variables like socioeconomic status and physical activity between Wq1 and Wq3. Overall, the low-fat diet resulted in more participants with long-term weight loss than the low-carbohydrate diet.

But the researchers were still curious why there was such a difference in weight loss results between Wq1 and Wq3 participants given that the difference in those groups was not due to dietary choices. As a result, they began to look for protein molecules in the blood that could be indicators of weight loss. For low-carbohydrate diet participants, having a lower amount of IDUA at the beginning of the study was related to long-term weight loss. This is a protein that helps break down GAGs, a group of sugar molecules that have been shown to lead to weight loss in mice. GAGs may have the same function in humans, and so when IDUA breaks down GAGs, it may be preventing weight loss.

A low amount of another protein called TNFRSF13B was also associated with long-term weight loss for the low-carbohydrate diet. This protein is related to immunity. In a previous study, if mice’s immune cells lacked TNFRSF13B, it prevented weight gain.

The researchers found that low levels of IDUA and TNFRSF13B, along with a few other proteins, were associated with weight loss in the HLC group. Many of these proteins were shown to be correlated with weight gain in the past. High levels of these proteins were associated with long-term weight regain. However, a high amount of TNFRSF13B protein was associated with long-term weight loss for the low-fat group. This indicates that the same protein may be related to weight loss in a different diet, pointing to different mechanisms for weight loss with different diets. Additionally, the quantity of certain proteins varied based on gender and body fat. This shows that weight loss is affected by many factors that vary based on the individual.

In this study, the researchers also wanted to find out the impact of the gut microbiome. They found that the types of bacteria in the gut were more indicative of weight loss than diet type. One surprising finding was that even before there was the implementation of any type of diet, those who ultimately had long-term weight loss had differences in gut bacteria types compared to the others. For example, those who achieved long-term weight loss had a higher likelihood of having Bacteroidaceae B. caccae and Lachnospiraceae Roseburia NA bacterial variants in the gut microbiome. Bacteroidaceae B. caccae is a species in the Bacteroides fragilis group, which has previously been shown to be highly present in those who consume a higher fiber diet. Furthermore, Lachnospiraceae Roseburia is a species in the Lachnospira group, which has previously been shown to be highly present in those with vegetable-based diets, as opposed to meat-based diets. These hint that plant-based and high-fiber diets long-term may result in beneficial mechanisms for long-term weight loss via their effects on the microbiome composition.

Additionally, this study found that Prevotellaceae P. copri bacterial variants are associated with a lack of long-term weight loss. Prevotellaceae P. copri is a species in the Prevotella group, which has previously been shown to be associated with a high-fiber diet. The Prevotella-pertaining findings of this study contradict other studies, because of the focus on a specific species. This indicates the need for further research on this topic. However, these findings further emphasize the importance of the gut microbiome on weight.

Broadening View:

Currently, 2.8 million people suffer obesity-related deaths every year. This has resulted in people trying a variety of different diets to reduce weight. However, it is essential to understand the biological mechanisms behind the effects of diet on weight. In this study, researchers found that more people in the healthy low-fat diet experienced long-term weight loss compared to those in the healthy low-carbohydrate diet. A key finding of this study was that merely restricting the number of daily calories is not enough for weight loss, but the types of calorie sources (e.g. type of fats or carbohydrates) are also important.

Overall, this study shows that short-term weight loss is related to dietary choices, but long-term weight loss is related to other aspects, such as the presence of certain proteins in the blood (which might point to genetic differences) and gut bacteria. This research demonstrates the importance of continuing to explore the biological pathways and processes that are triggered by different types of diets, paving the way for future weight loss studies.

Badri Viswanathan is a senior at Hillsdale High School. He is extremely interested in the promise of genomics and other scientific breakthroughs, especially as pertaining to cardiology. He is the founder and president of a club at his school called Medicine for Us!, in which scientific literature is condensed and analyzed. This research is then shared to the community through monthly presentations.

In collaboration with the Stanford Healthcare Innovation Lab, he furthers his mission by analyzing promising new findings, such as multi-omics research. Badri hopes to be a cardiologist and conduct research one day.

Works Cited:

Li, X., Perelman, D., Leong, A. K., Fragiadakis, G., Gardner, C. D., & Snyder, M. P. (2022). Distinct factors associated with short-term and long-term weight loss induced by low-fat or low-carbohydrate diet intervention. Cell reports. Medicine, 3(12), 100870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100870

Additional Resources:

“Eat Smart – Fats – Saturated Fat.” American Heart Association, 1 November 2021, https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/fats/saturated-fats.

“IDUA gene.” MedlinePlus, 1 December 2008, https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/idua/.

Joshi, Shilpa, and Viswanathan Mohan. “Pros & cons of some popular extreme weight-loss diets.” Indian Journal of Medical Research, 2018. National Library of Medicine, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6366252/.

Kit Yeoh, Yun, et al. “Prevotella species in the human gut is primarily comprised of Prevotella copri, Prevotella stercorea and related lineages.” Scientific Reports, 2022. Nature, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-12721-4.

Liu, Lunhua, et al. “TACI-Deficient Macrophages Protect Mice Against Metaflammation and Obesity-Induced Dysregulation of Glucose Homeostasis.” Diabetes, 2018. National Library of Medicine, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6054430/.

Nakajima, Akihito, et al. “A Soluble Fiber Diet Increases Bacteroides fragilis Group Abundance and Immunoglobulin A Production in the Gut.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2020. National Library of Medicine, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7301863/.

“Obesity.” World Health Organization (WHO), 9 June 2021, https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/6-facts-on-obesity.

Reynés, Bàrbara, et al. “Anti-obesity and insulin-sensitising effects of a glycosaminoglycan mix.” Journal of Functional Foods, vol. 26, 2016. ScienceDirect, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1756464616302171.

“TNFRSF13B gene.” MedlinePlus, 1 May 2016, https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/tnfrsf13b/.

“Types of Fat | The Nutrition Source | Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.” Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/what-should-you-eat/fats-and-cholesterol/types-of-fat/.

Vacca, Mirco, et al. “The Controversial Role of Human Gut Lachnospiraceae.” Microorganisms, 2020. National Library of Medicine, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7232163/.